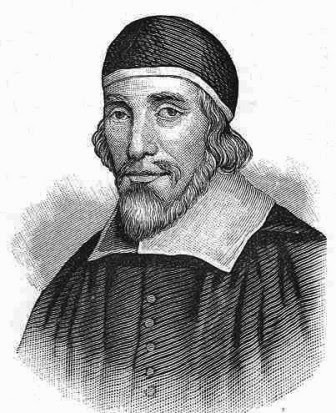

EVEN though Farewell Sermons had been preached in many parishes on Sunday, August 17, there was a widespread feeling of uncertainty throughout the nation with regard to the direction and character of coming events. Something of this uncertainty can be detected in the words of some of the sermons that were preached on that day. We find, for example, Thomas Watson saying to his people in his morning sermon, “I will not promise that I shall still preach among you, nor will I say that I shall not, I desire to be guided by the silver thread of God’s Word, and of God’s providence.” But, on the other hand, speaking on the same day in another London church, Thomas Lye said, “It is most probable, beloved, whatever others may think, but in my opinion (God may work wonders) neither you nor I shall ever see the faces of, or have a word more to speak to one another till the day of judgment.” The variation between these two statements does not mean that Lye was more resolute than Watson in his decision not to subscribe to the Act of Uniformity, on that point they were both equally firm; but there lies behind the words of the preachers a differing degree of uncertainty whether or not the Act would actually be enforced against them.

They were not without grounds for hopefulness, for although the Act had been passed by Parliament, the King could still exercise his clemency in an Act of Indulgence by which at least some of those who failed to conform might be allowed by the royal prerogative to retain their churches. For Clarendon, the King’s minister, had just promised such a favour to Manton, Bates, Calamy and other Puritans, provided they petitioned the King for it. This news would doubtless be circulated and discussed amongst the London ministers and word of it was carried to the country. The diary of John Angier, the Lancashire Puritan, carries this entry in the week preceding Bartholomew’s Day: “August 20 was a day of general seeking God in reference to the state of the Church; that very day several ministers were before some of the Council and received encouragement to go on in the ministry. A letter read to them from the King to the Bishops that no man should be troubled for Nonconformity at least till his cause was heard before the Council. The news came to Manchester by Saturday post and was that night dispersed by messengers sent to several places. By means hereof many ministers that intended not to preach fell to their work, which caused great joy in many congregations.” Similarly, Henry Newcome of Manchester writes in his diary on Bartholomew’s Eve, “I received a letter from Mr. Ashurst which gave us an account that past all expectation there was some indulgence to be hoped for in some cases.”

Clarendon’s promise was not merely a device to ease the tension in the nation till Bartholomew’s Day was passed. [1] He and the King had also grounds for uncertainty. They were not sure what the political repercussions of a wholesale ejection of the Puritans might be; the number of the nonconforming clergy was still unknown, although it was evident they would include some of the most eminent names in the land; and there was the fear lest the powerful Presbyterian party might make common cause with the Independents and thus, in Clarendon’s words, “give a great shock to the present settlement.” Charles, however, was also busy with other affairs. The previous May he had married Catherine of Braganza, and Saturday, August 23, was the day appointed for her public arrival and welcome at Whitehall. Amidst a brilliant regatta of barges and boats, the King and his Roman Catholic Queen sailed down the river from Hampton Court; “music floated from bands on deck, and thundering peals roared from pieces of ordnance on shore”. “I was spectator,” wrote John Evelyn in his diary, “of the most magnificent triumph that ever floated on the Thames.” But there were many in London that day that had no heart for the festivities. Far removed in thought from the colour and pageantry of the Queen’s arrival, a great company of silent and mourning believers was gathered in the parish of St. Austin’s for the burial of Simeon Ashe. Ashe had long been one of the popular Puritan leaders and “he went seasonably to heaven,” says Calamy, “at the very time when he was cast out of the Church. He was bury’d the very even of Bartholomew-Day.” The historian’s grandfather, the veteran Edmund Calamy of St. Mary Aldermanbury, was naturally the preacher on such an occasion, and that day he preached a sermon that was to be spoken of and read over for many years to come. His text was Isaiah 57:1, “The righteous perisheth, and no man layeth it to heart, and merciful men are taken away, none considering that the righteous are taken away from the evil to come.” The sermon is one of the finest examples of Puritan preaching, and though it does not strictly belong to the Farewell Sermons it is not surprising that it was given a place in the volume that was shortly to bear that title. Though Calamy packs his exposition with doctrines, he so blends his teaching with illustration, and his reproofs with exhortations, that he was in no danger of losing the attention of his hearers. Take the following example: ...

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg/220px-Thomas_Watson_(Puritan).jpg)